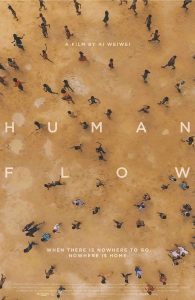

Every day thirty-four thousand people flee their homes to escape famine, poverty, and war. Every day thousands of families become refugees. But those are just numbers. And numbers don’t move us. Real stories of real people do. That’s why Human Flow, an epic documentary by the provocative Chinese contemporary artist and activist Ai Weiwei, is so powerful and so important.

The scale and devastation of the global refugee crisis is expansive, but Weiwei is an able guide, taking viewers around the world and introducing us to real people—real image-bearers of God—along the way. He doesn’t focus on the causes of the crisis; rather, he offers a compelling and compassionate window into a world of deep suffering.

This is a world most of us have no access to, a reality that’s an ocean away. But, even if we think we’re comfortably insulated from this crisis, the world Weiwei reveals is the world in which we live too. It’s a reality we shouldn’t ignore.

Weiwei guides viewers through refugee camps and war-torn cities to see, listen, and learn. The majority of the dialogue comes through testimonials of individuals who are displaced, relief workers who are striving to bring aid, and political leaders who are attempting to address the global crisis. Throughout the film, there is an overt tension between the beauty of the cinematography and the horror of the crisis being captured on film. It is, at the same time, captivating and overwhelming.

When Home Is Taken from You

It takes you roughly as long to watch the film as it took Rafik Ismail, and thousands of other refugees like him, to make the dangerous journey from Myanmar to Bangladesh. But even though crossing from one border into another didn’t take long, Ismail will be processing the experience of losing everything the rest of his life.

“We didn’t want to go to another country,” he explained. “Our forefather’s land has been taken from us. Our livestock has been taken. There’s nothing left. It is all gone. Rohingya women have been raped; thousands have been raped and killed. Yet we still remain loyal. We do not want to fight [the soldiers] with force because we are Rohingya. . . . We too are humans.”

“Being a refugee is much more than a political status. It is the most perverse kind of cruelty that can be exercised against a human being.”

By presenting a vivid portrait of worldwide wandering, Human Flow is a primer on the worldwide effects of conflict, poverty, and climate change on the displacement of families like Rafik’s. In a press interview for his film, Weiwei said he began the documentary after watching a boat of immigrants come ashore in Greece. He set out to find a visual language through his art that would allow him to respond to the situation.

The film takes viewers through twenty-three countries, asking us to witness the suffering that forces people to flee their homelands. It brings the pain of the refugee experience into sharp focus while reminding us that refugees are not migrants. They don’t elect to move—they are driven out.

According to the UN Refugee Convention, a refugee is defined as an individual with “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” There are currently 22.5 million people worldwide who, according to this definition, have been given refugee status.

Are We Immune to Disaster? An Unexpected Message for Us

Although Weiwei does not bring a religious angle into the documentary, there are many messages in the film that may speak to Christian viewers. Chiefly, there is a call to see the humanity of every person and the dignity endowed in every human heart. Though refugees have lost their homes, their possessions, and their communities, they have not lost their worth.

The many testimonies in the film remind us of a truth expressed most eloquently by activist Hanan Daoud Khalil Ashrawi, that “being a refugee is much more than a political status. It is the most perverse kind of cruelty that can be exercised against a human being by depriving the person of all forms of security, the most basic requirements of a normal life. . . . You are forcibly robbing this human being of all aspects that would make human life not just tolerable, but meaningful.”

The refugee crisis bears within itself manifold disasters, including dehumanization. This particular disaster is one aspect of the crisis that even touches us.

“Ignoring refugees can be an extension of the desire to ignore our own susceptibility to suffering and the inevitability of death.”

In the mid-twentieth century, a pastor who had endured displacement wrote,

Multitudes as numerous as whole nations still wander over the face of the earth or perish when artificial walls put an end to their wanderings. All those who are called refugees . . . belong to this wandering. . . . Such people carry in their souls, and often in their bodies, the traces of death, and they will never completely lose them. . . . Receive them as symbols of the finiteness and transitoriness of every human concern, of every human life, and of every created thing.

I suspect that the world’s denial of the dignity of refugees is the result of being confronted with unsettling “traces of death.” The refugee crisis is an affront to the naïve belief that we can avoid war, pain, and even death through our own ingenuity and hard work—through education, medicine, or technological advance. But ignoring refugees can be an extension of the desire to ignore our own susceptibility to suffering and the inevitability of death. If we avoid these basic realities, we ultimately dehumanize ourselves in the process.

Refugees are a reminder of the tenuousness of human existence. They disturb our attempts to deny our own finitude by forcing us to acknowledge that, from the standpoint of the human condition, we’re not so different.

The Dignity within All of Us

Human Flow captures the beauty and dignity of every human being, including those labeled as refugees. In this sense, the film reminds us of a fundamental Christian truth: that every human irrevocably bears the image of God. As followers of Jesus, it’s time for us to come to grips with the reality that we bear a responsibility to care for refugees in the name of Jesus. That care takes many forms, but all are predicated on the belief in the God-given dignity of every human.

When Jesus looked at the oppressed and downtrodden, he looked at them with compassion (Matt. 9:36; Matt. 14:14; Luke 7:13). The compassion of Christ is part of the essential attire for every disciple (Col. 3:12). It is the compassion of Christ that moves men, women, and families, to enter the tumult of the global refugee crisis on mission.

Some enter by moving to a foreign land and joining the oppressed, bringing them the good news of Jesus (Isa. 61:1; Luke 4:18). Others enter through sacrificial giving to relief efforts. Some by praying for those caught up in the tragedy and for those who minister among them. Regardless of how we enter the crisis, every follower of Jesus is called to enter into the compassion of our Lord and to see all people, including refugees, with his eyes.

Ai Weiwei speaks only a handful of times during the documentary. But one of his exchanges with a refugee named Abdullah sums up the message of the film. The director smiles and says to him, “I respect you.”

The unspoken question hanging in the air is, do we?

Jeffrey Heine is pastor of teaching and discipleship at Redeemer Community Church in Birmingham, Alabama. A graduate of Murray State University in Kentucky, Jeff went on to get his MDiv and DMin at Beeson Divinity School in Birmingham, Alabama.