Editor’s Note: The history of missions is replete with examples of God using his Word to call his followers to engage in his redemptive work around the world by praying, giving, going, and sending. The aim of this article series (part one here) is to help Bible students, teachers, and readers recognize the theme of global missions throughout Scripture.

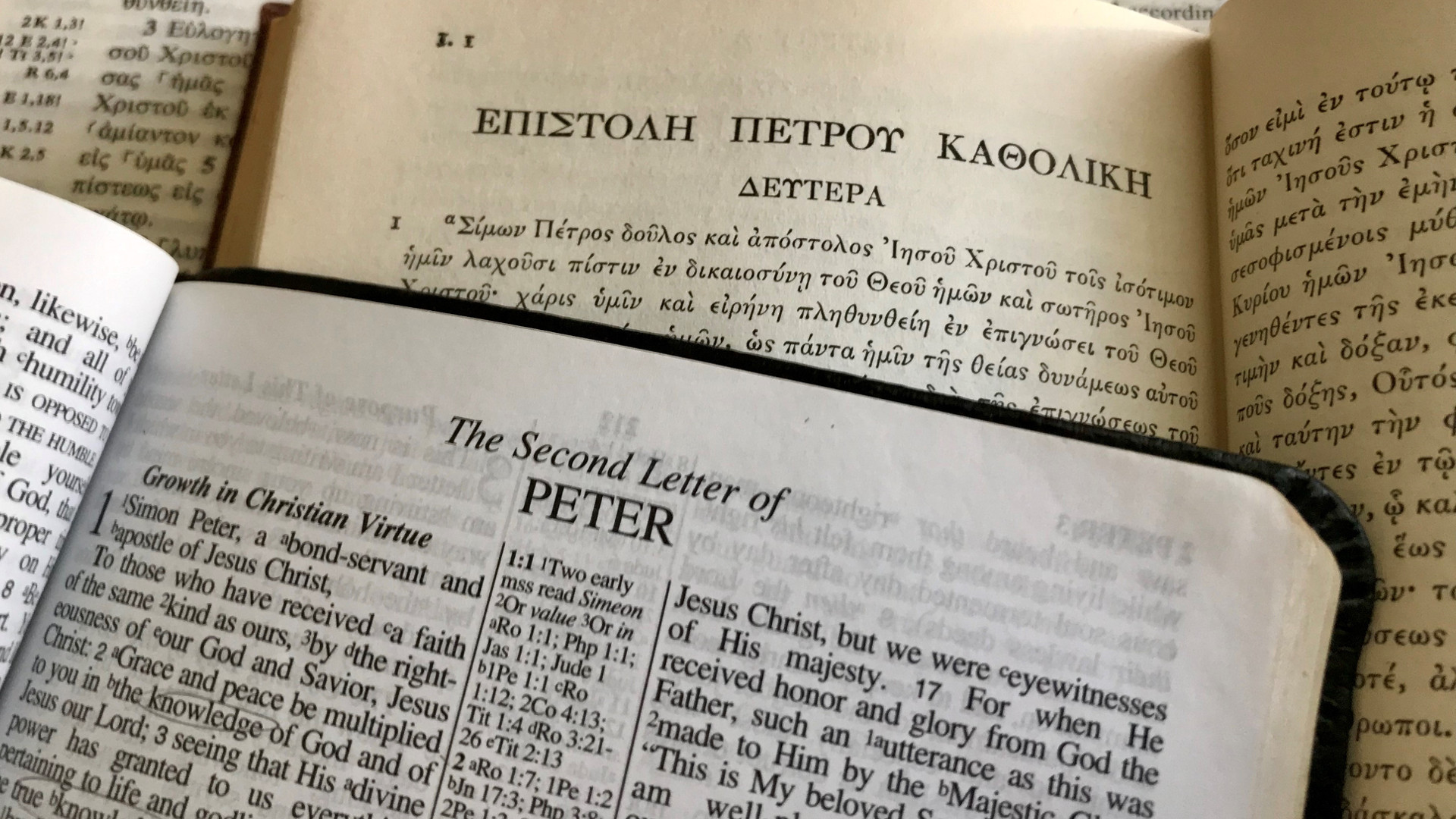

The apostle Peter’s letters to the churches of Asia Minor are missionary literature. They essentially teach Christians how to live as missionaries—that is, as “sojourners and exiles” (1 Pet. 2:11 ESV). Dr. Eckhard Schnabel describes how Peter instructed his readers residing in a non-Christian society on how to live as a new community of people who have a discernibly different lifestyle than the people who surround them (1522).

The apostle Peter’s letters to the churches of Asia Minor are missionary literature. They essentially teach Christians how to live as missionaries—that is, as “sojourners and exiles” (1 Pet. 2:11 ESV). Dr. Eckhard Schnabel describes how Peter instructed his readers residing in a non-Christian society on how to live as a new community of people who have a discernibly different lifestyle than the people who surround them (1522).

Four ways in which the missional emphasis of 1 and 2 Peter is expressed are through the themes of identity, lifestyle, message, and hope.

An Identity to Embody

Throughout the book of 1 Peter, his primary concern is who God’s people are—their missional identity—and how they are to live out that identity in relation to an unbelieving world as God’s holy people (1 Pet 1:15-16, 1 Pet 2:5, 1 Pet 2:9). Perhaps more than any other book, 1 Peter spotlights the need for what one writer has called “missional holiness.”[1]

Peter’s twin emphasis on holiness and mission is best summed up in his description of these Christians as “exiles” and “sojourners” (1 Pet. 1:17; 2:11 ESV). Peter applied the exile or “temporary resident” (1 Pet. 2:11 HCSB) metaphor to a primarily Gentile group of Christians. By using this metaphor to describe their status in the world, Peter was integrating this group of Gentiles into Israel’s storyline. In essence, these alien residents were described by Peter as being like Abraham, Moses, and Israel—people who lived displaced lives, the lives of refugees and immigrants in the world.

It’s important to see that the new identity as alien residents Peter indicated did not mean a retreat, departure, or calculated isolation from society. The alien resident nature of these Christians in Asia Minor did not engender an escapist mentality. Rather, it propelled them into the culture as salt and light for the spread of the gospel. As one Bible scholar helpfully notes, “It appears that Peter’s entire vision of the church’s mission takes its cue from the Old Testament concept of Israel as a mediatorial body, a light to the nations, thus revealing God’s glory (Ex. 19:6; Isa. 43:20).”[2]

Peter perceived the church’s presence in the world from the vantage point of mission, stressing its identity as a witnessing community. Fundamentally, who we are in terms of our identity as Christians shapes the course of our mission. Therefore, knowing our identity as alien residents called to live a life a holiness is the place we must begin if we are to effectively live in the world as Christ’s sent out ones.

A Lifestyle to Embrace

Flowing out of the identity of alien residents called to live holy lives is a distinct lifestyle for Christians to embrace. Who we are determines how we live. Alien residents set apart by God to embody a holy identity will inevitably live distinct lives in the world. In essence, the root of dedication to God leads to the fruit of doing good in the world and making a positive difference (2 Pet. 1:3).

Peter called and exhorted his readers to live a life of good works among the Gentiles (1 Pet. 2:12; 3:16–17). He recognized the evangelistic impact of a Christian community engaging in a lifestyle of doing good (1 Pet. 3:1–2).[3] Whether the good works emphasized by Peter stimulated an evangelistic effect, Peter at a minimum saw that good works had an impact on a watching world. God’s people, living in predominantly non-Christian environments, are to live out and embrace a lifestyle of good works and Christian conduct.

“For Peter, the witness of word and life are inseparable. Those who have been changed by the gospel cannot help but speak and share the gospel.”

A Message to Proclaim

The emphasis on good conduct in 1 and 2 Peter might lead some to assume that verbal witness was not a priority for Peter in these letters. On the contrary, Peter contended that verbal proclamation of the gospel is central to Christian witness and mission in the world. Peter actually gave considerable attention to the need for gospel proclamation, making three clear mentions of the nature and role of verbal proclamation in Christian mission in his first letter (1 Pet. 1:12; 2:9; 3:15). In short, the witness of word and life are inseparable in 1 Peter.[4]

Those who have been changed by the gospel cannot help but speak and share the gospel. Living a distinct lifestyle in the culture will inevitably provoke questions and inquiries from those in society. As a result, alien residents must be able to give a verbal testimony, defense, and response to those who ask about their distinct and contrasting behavior and beliefs.

A Hope to Endure

Two themes that appear frequently in 1 and 2 Peter are suffering and hope (1 Pet. 4:1–19; 2 Pet. 3:1–10). Peter’s message to alien residents throughout the book is consistent and clear. As followers of Christ in the world, they will endure suffering, but they do not endure suffering without hope (1 Pet. 1:11; 2:19–23; 3:14–17; 4:1; 4:13, 4:15–19; 5:1; 5:9–10; 2 Pet. 3:3–5).

The two themes of suffering and hope, though vastly different, do go together in Peter’s letters. The suffering of the saints reminds them of their present purpose and future hope. Gordon Kirk argues, “Slander, insult, persecution, trouble, affliction, or any type of suffering is limited to the temporal realm . . . a future inheritance is yet to come. Hope, or something to look forward to, gives people reason for enduring hardships. Christians have the invincible promise of ultimate victory which cultivates unwavering endurance.”[5]

Peter pointed to a hopeful promise—the hope of heaven and the promise of a renewed and restored earth that enables alien residents to endure suffering and hardship in this life (2 Pet. 3:13).

The Missionary Letters of 1 and 2 Peter

The books of 1 and 2 Peter, then, are best understood as missionary literature. The letters were written to instruct Christians on how to faithfully display the gospel in a context of hostility and opposition. The timeless truths conveyed by Peter in these letters remain instructive and engender hope and perseverance for Christians living on mission today. In the end, the hope for a renewed and restored creation is the foundational motivation for why Christians can labor to live a life of joyful endurance as they embody a new identity, embrace a new lifestyle, and explain an urgent message as they await the return of their King.

Dr. Paul Akin is the team leader of assessment and deployment at the IMB. He can be found on Twitter @Pakin33.

[1] Dean Flemming, “‘Won over without a Word’: Holiness and the Church’s Missional Identity in 1 Peter,” Wesleyan Theological Journal 49, no. 1 (2014): 50–51.

[2] Andreas Köstenberger, “Mission in the General Epistles,” in Mission in the New Testament: An Evangelical Approach, ed. William J. Larkin Jr. and Joel F. Williams (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1998), 202–203.

[3] Dean Flemming, Why Mission? (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2015), 100–101.

[4] Dean Flemming, “‘Won over without a Word: Holiness and the Church’s Missional Identity in 1 Peter,” Wesleyan Theological Journal 49, no. 1 (2014): 61.

[5] Gordon Kirk, “Endurance in Suffering in 1 Peter,” Bibliotheca Sacra 138, no. 549 (1981): 55.