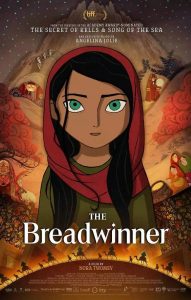

Before I sat down to watch The Breadwinner, I couldn’t tell you the last time I watched an animated movie about people—the human kind. People without magical powers. Or talking animal friends. In that sense, Nora Twomey’s Academy Award-nominated film about an Afghan family torn apart by war feels counter-cultural right out of the gate. People fill each frame—real, recognizable, relatable people. Indeed, The Breadwinner offers a well-crafted and heartfelt alternative to the glossy, powerhouse movies the major studios have distilled to a science.

Set in Taliban controlled Kabul, the film follows a young girl named Parvana as she and her family try to endure injustice and hardship. When Parvana’s father is arrested, her mother is left at home with two teenage daughters and a baby boy. They have to fend for themselves in a city where women aren’t allowed in the streets without being accompanied by a male relative. So Parvana cuts off her hair and dresses as a boy in order to navigate life in Kabul, earning money and keeping her family from starvation.

Given that The Breadwinner is an animated feature, parents will naturally wonder if it’s family-friendly fare. It is appropriate for older children and teens, but the film works from a different emotional map than your average blockbuster. Unlike the expected formula of “tell an entertaining kid story while building in enough jokes and subtext that sail over the kids’ heads while making the grown-ups laugh and cry,” The Breadwinner wants viewers to wrestle with grown-up emotions. The film honestly depicts the cruelty of Taliban rule, but it is not graphic. There will be a lot to talk about with your kids if you watch the film together.

Given that The Breadwinner is an animated feature, parents will naturally wonder if it’s family-friendly fare. It is appropriate for older children and teens, but the film works from a different emotional map than your average blockbuster. Unlike the expected formula of “tell an entertaining kid story while building in enough jokes and subtext that sail over the kids’ heads while making the grown-ups laugh and cry,” The Breadwinner wants viewers to wrestle with grown-up emotions. The film honestly depicts the cruelty of Taliban rule, but it is not graphic. There will be a lot to talk about with your kids if you watch the film together.

Familiar Emotions in a Foreign Culture

What makes The Breadwinner succeed as a film also makes it valuable for Christians who wish to think seriously about mission. The film elicits genuine empathy for its characters. Quiet moments of grief counterpoint moments of delight, kindness, and love as the relationships between the characters develop in the shadow of tension and danger. As Parvana and her family struggle on the margins of poverty and violence, we are drawn into an emotional world surprisingly familiar, even if we might have presumed Afghan culture would feel foreign. We are invited to weep with the people we meet and rejoice in their small moments of joy.

“From a Christian perspective, God’s kingdom isn’t a battlefield. It’s a feast.”

The film does not confine our empathy only to Parvana and her family. All of the characters in The Breadwinner are complicated and worthy of deep consideration, including the merchants in the town—even, somewhat scandalously, some in the Taliban membership who seem to have gotten themselves wrapped up in more than they bargained for. In stretching our empathy even to within scalding distance of Taliban fighters, The Breadwinner makes the bracing assertion that a human heart beats in everyone. Even someone we would write off as a villain may bear the same weight of human grief that we all bear.

The Breadwinner’s suggestion that each individual has an ineffable human core grounds the film in familiar territory for a Christian. People are reachable. Doesn’t the notion that people are in need of redemption animate the very heart of our mission? Just imagine telling a girl who must cut off her hair and masquerade as a boy just to walk the streets unharmed that in God’s kingdom she will have the full rights and standing of a son (Eph. 1:5). In God’s eyes, she is every bit as worthy and valuable as a male.

Coercion or Compassion: The Mission of the Taliban or the Mission of the Church?

While the empathy The Breadwinner inspires should motivate Christian mission, as I reflected on the film I also sensed a warning. There are two kinds of mission—one is coercive while the other frees. One mission is characterized by unending clash and clamor for the power to coerce. We see that mission in the Taliban and it bears bitter fruit. The unifying sense you get from all the Taliban devotees in the film is that they’re all just really angry. When they see a law broken, they shout and harass. They quash and exile those they believe defile their society. Life with such neighbors seems intolerable.

“There are two kinds of mission—one is coercive while the other frees.”

As Christians who witness to our faith, if we traffic in anger and outrage in the style of the Taliban then people might get a whiff of that same old power struggle and brace themselves for attack. If we hope to be received as people who carry good news, we better look higher than the maelstrom, and that means embracing compassion while holding to an eternal hope in Christ. Then we’ll be offering living water in a desert.

Come to the Table

At the start of the film, Parvana’s father says that Afghans have always been caught between various wars of various kings—the Taliban is simply the latest to come through town. All these leaders have been vying for power that always defines itself by who they can exclude, subjugate, and kill. Her father encourages her to take heart because power passes back and forth and happier times may return unexpectedly. Of course, the downside to such a tenuous hope is the power struggle causing all the havoc could just as easily bring worse circumstances.

This, I think, is where The Breadwinner is most open to a Christian response. From a Christian perspective, God’s kingdom isn’t a battlefield. It’s a feast. We don’t have to fight our way into eternal rest because grace invites us to the table. So, while we endure hardships, we endure as people who can already taste spiritual fruit. Perhaps the most unexpected fruit is that we can leave judgment in the hands of God. We can go ahead and beat our swords into plowshares and, so far as it depends on us, live in peace with our neighbors (Isa. 2:4).

In revealing the painful consequences of The Taliban’s mission, The Breadwinner prompted me to consider a different approach. The film invited me to see an oppressed people, to feel compassion for them, and to feel kinship with them as fellow image bearers of God—not to write them off or shout them down, but to invite them in.

As The Breadwinner ended, I found myself thinking of Ephesians 6. Ours is not an unending struggle for power in this world. Our struggle is against evil spiritual forces that animate people who want to crush others. Our good news is not the eventual eradication of every sin and sinner. Our good news is that reunion with God is possible. Jesus has made a way and has laid out a feast. We go out into the streets and call out, “Come to the table!”

Editor’s Note: The Breadwinner is rated PG-13. It depicts incidents of conflict and violence that are not graphic but may be disturbing to young children. Currently, you can buy or rent The Breadwinner to watch online on various video streaming services.

Michael Morgan lives and writes in Louisville, Kentucky, where he and his wife raise their two boys. He is a member of Sojourn Community Church where he serves as a musician and liturgy writer for the worship team. He has written for The Gospel Coalition, Christ and Pop Culture, and In Touch Ministries.