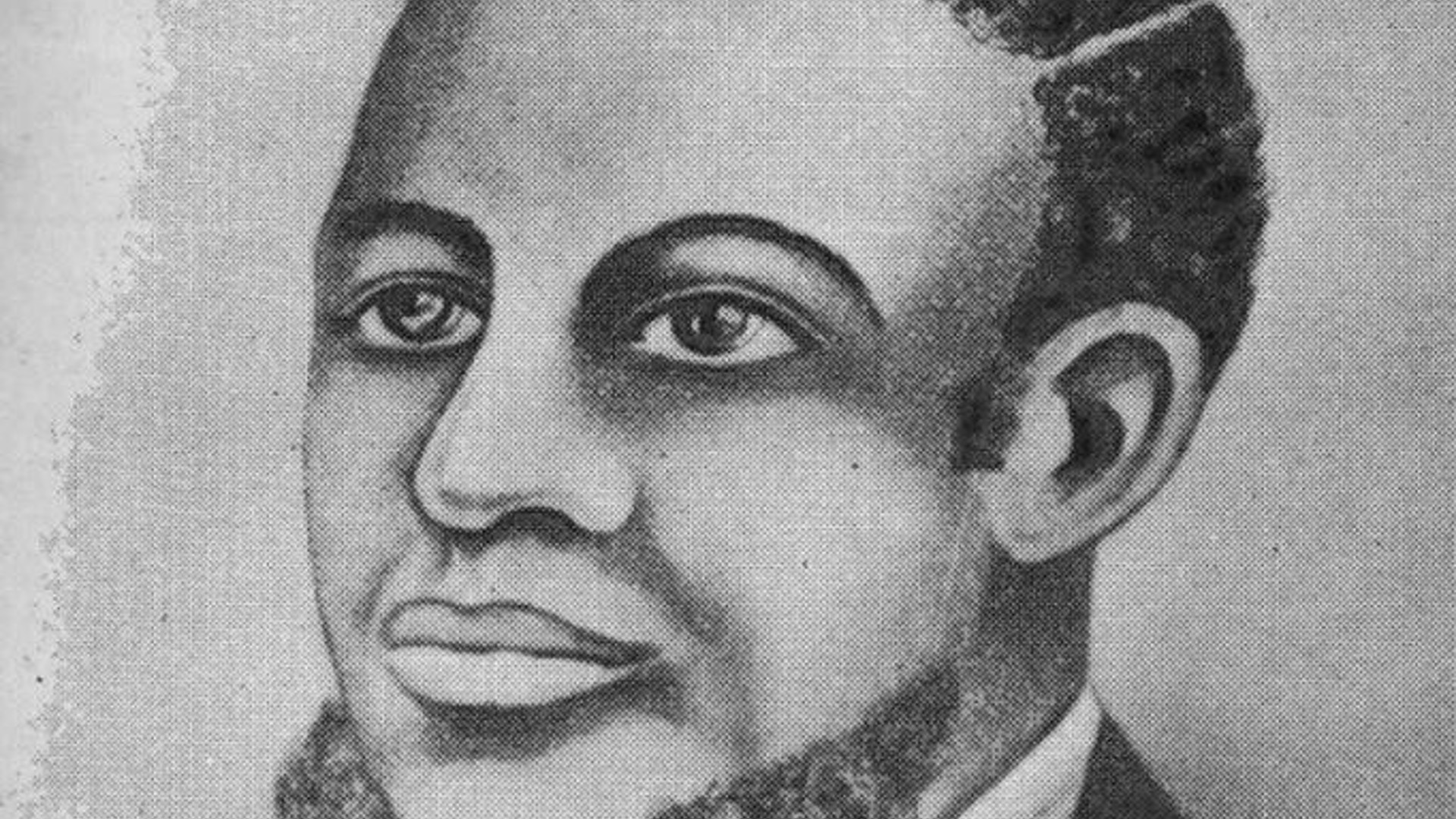

Lott Cary was the first African-American missionary to Africa. He was responsible for the missionary movement that created a growing interest among African-Americans in the evangelization of Africa, as well as other parts of the world.

Lott Cary was the first African-American missionary to Africa. He was responsible for the missionary movement that created a growing interest among African-Americans in the evangelization of Africa, as well as other parts of the world.

Early Life and Conversion

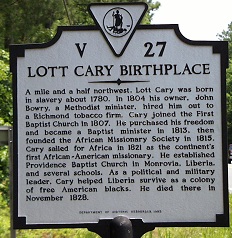

Lott was born in 1780 in Charles City County, Virginia, on the estate of William A. Christian. Unlike most slave families, Cary’s family was able to live together. His father, mother, and grandmother were God-fearing and faithful Baptists. Not only was his grandmother, Mahala, an important caretaker, she was also responsible for shaping Lott’s religious beliefs.

When he was twenty-four years old, Lott’s owner sent him to Richmond, Virginia, to work in a tobacco warehouse. While there, he drank too much, started swearing, and running around like the other men. However, after being there two or three years he felt conviction for his sin and became a Christian. He was converted in the First Baptist Church after hearing a sermon about Nicodemus.

After professing faith in Christ, he was baptized and became a member of the church. Lott could not read but he was so moved by the story of Nicodemus that he wanted to read it for himself. He went to night school and studied reading, writing, math, the Bible, and current events.

“Lott Cary’s legacy includes American Christians of all races taking the gospel through the entire continent of Africa.”

Call to Ministry and to Africa

After a short time, Lott was given the job of supervisor in the warehouse. This job provided him enough money to buy his freedom. Eventually, Lott felt called to ministry and the First Baptist Church licensed him to preach. He preached across the state of Virginia. A frequent topic of conversation and theme of his sermons was a missionary call and the needs of Africa.

In 1815, Cary worked with several other men to organize the Richmond African Baptist Missionary Society. Lott served as the society’s first secretary and prayerfully sought to know God’s will for himself—whether he ought to stay or go.

Over time, Cary felt an increasing call to go to Africa. He believed he could serve God more effectively there because he would not face the same racism he did in the United States. In obedience to this call, Lott Cary left spiritual and economic comforts to serve as a missionary to Africa.

Ministry to Africa

On January 23, 1821, Lott Cary and his family, Collin Teague, and Joseph Langford left America to establish an African mission. After they arrived in Sierra Leone, they were confronted with financial difficulties when they discovered that the American Colonization Society had neglected to purchase land, which left the team without any means of support. To survive, Cary and the others worked as farm laborers while they awaited support from back home.

In December 1821, a full year after they arrived in Africa, the land purchase was finally completed. Along with the financial difficulty, however, Lott’s wife died, leaving him with the responsibility of caring for his three children alone.

In conjunction with his missionary activities, Cary served as health officer and government inspector in Liberia. While in Liberia’s capital, Cary pastored several churches and established the Monrovia Mission Society among the Liberian Christians to raise support for missions and communicate the need to Christians in America. Cary envisioned Liberia as the starting point for taking the gospel to the whole continent.

Road marker in Charles City County, Virginia (US National Park Service, nps.gov)

Road marker in Charles City County, Virginia (US National Park Service, nps.gov)

Untimely Death and Lasting Legacy

Cary became the acting governor of Liberia in 1826 but was killed in an accidental explosion that occurred when he and some other men were preparing cartridges to defend their colony from native tribes.

Lott Cary only served in Liberia for approximately eight years. His dream of seeing the gospel spread throughout Africa did not happen in his lifetime. But because of his efforts, Liberia is a free nation today and the American Baptist Missionary Convention continues to send men and women like him to take the gospel to other lands.

His missionary productivity may seem small, but his legacy was more significant than he ever imagined. According to Mark Sidwell, “As important as Lott Cary was as a ‘founding father’ of an African republic and as an inspiration to African-American Christians, even more notable was his example to Christians of all races. Cary became the forerunner to Christian work across the continent of Africa” (p. 50).

Lott Cary’s legacy includes American Christians of all races taking the gospel through the entire continent of Africa.