The exquisite Chinese porcelain vases would have been beautiful if the paintings in cobalt blue on their glazed surfaces hadn’t been so tragic. Families flee as their homes burn, a boy drowns in the sea, shell-shocked families crowd into tents in camps fenced off by razor wire—these are scenes of the refugee crisis on display in Ai Weiwei’s artwork, “The Odyssey.”

Ai Weiwei is the most celebrated Chinese artist working on the international scene today. His name was popularized when he helped design the Bird’s Nest Olympic Stadium in Beijing for the games hosted by China in 2008. The scale of his work is often breathtaking, like the 100 million handmade porcelain sunflower seeds created to fill the floor of the Tate Gallery in London.

When I traveled to visit Ai Weiwei on Porcelain, currently on exhibit at the Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul, Turkey, I expected work that was challenging and strident—art unapologetic about conveying a strong message. But I did not expect to be so moved by the fragile beauty of art that wrestles with a human tragedy.

Ai Weiwei’s work often plays on paradox. And “The Odyssey” succeeds precisely at the point of tension between the delicacy of classical Chinese painting and the heart-rending reality to which the work testifies.

Visualizing the Refugee Crisis

Six vases were laid out at the front of the gallery, each highlighting a different scene or stage of the refugee experience. Soldiers occupy a town and gun down civilians. Homes burn as families flee. Mothers and fathers stumble over mountains as they carry their children. Waves crash over people crowded into rafts never designed to hold so many as a boy falls overboard and drowns in the dark sea. Families languish while living in makeshift tents. Destitution and despair breed more violence.

“The Odyssey” by Ai Weiwei (2017) exhibited at Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul, Turkey.

Six themes—war, ruin, journey, crossing the sea, refugee camps, and uprisings—are repeated throughout the gallery. They appear on the individual vases displayed at the front. They decorate columns of stacked vases always arranged in the same progressive order, starting and ending with violence. Variations of similar imagery are printed in black and white onto paper covering the walls, a never-ending cycle of human displacement, trauma, and suffering.

Standing in the gallery, I felt as if these images surrounded me like elegant barbed wire. Sure, I’ve seen segments of the refugee journey captured in photographs and video, but I’ve never been immersed in the whole odyssey like this. It seems awful that the paintings on the vases are so gorgeous.

Historically, porcelain has been one of China’s prized exports and most precious art forms. In Ai Weiwei’s hands, the beauty of classical Chinese painting becomes a subversive vehicle for asking us to look closely at an ugly present reality: the traumatic journey of millions caught up in the largest migration since World War II. These paintings, in a style that was once intended to glorify the “benevolence, virtue, and majesty” of the Ming dynasty, prompt us to wonder whether those traits characterize the international response to this humanitarian crisis.

A painting depicting refugees crowded into a raft on a stormy sea in “The Odyssey” by Ai Weiwei (2017).

The refugees immortalized on the vases could be from anywhere. They could be Syrian, North African, Rohingya—there are so many flash points in the world where conditions are so dangerous that families face the terrible choice of staying and dying or fleeing and drowning or starving. Families around the world are trapped between the violence of war on one side and closed borders on the other.

Shattering the Cycle of Suffering

Ai Weiwei is a creator, but he’s also been known for breaking things. In 1995, he photographed himself dropping and shattering a two-thousand-year-old Han dynasty urn, an iconoclastic act that evoked memories of the destruction of priceless art during the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

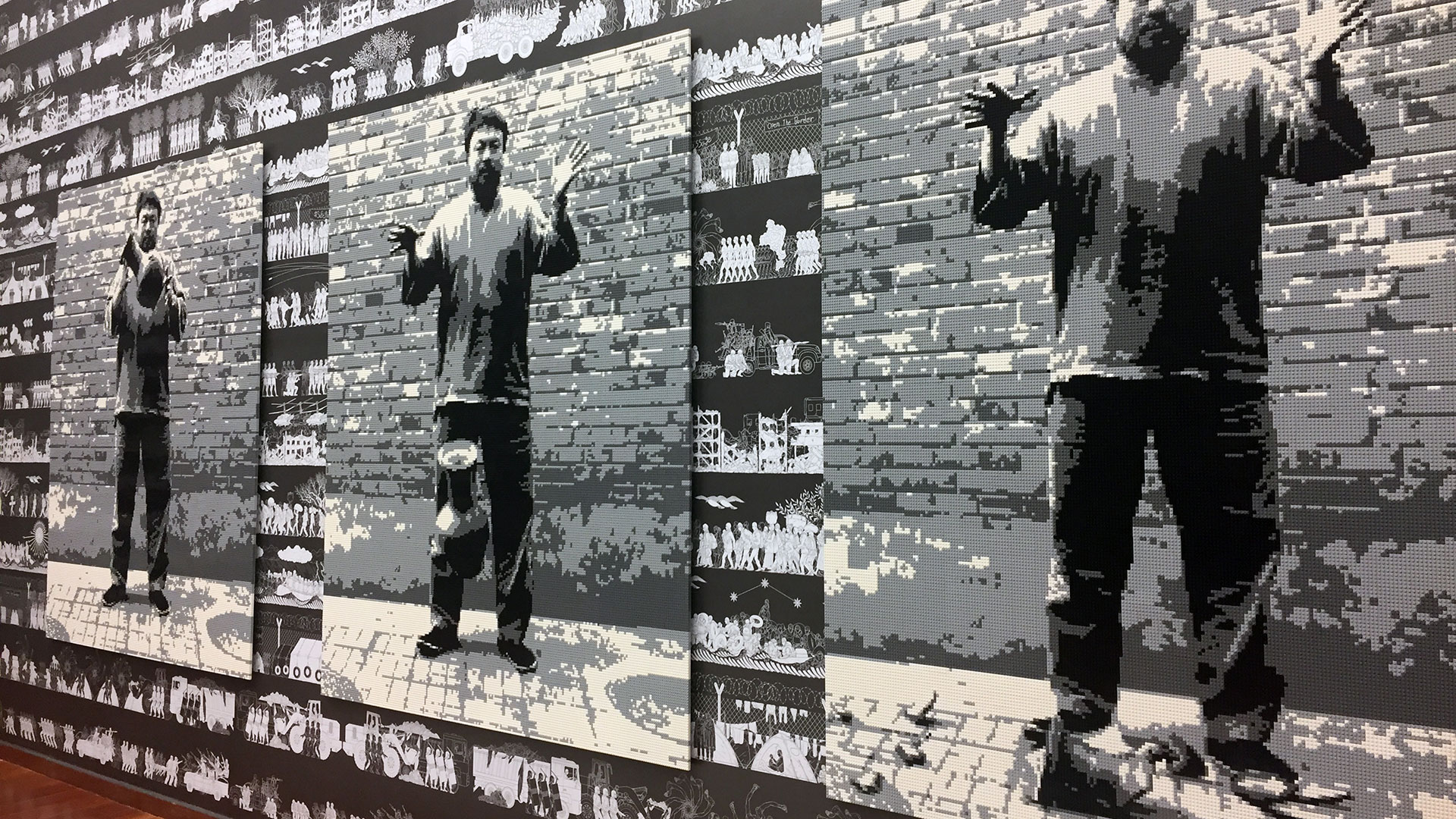

Three images crafted from Legos show the artist dropping and shattering a vase in “The Odyssey” by Ai Weiwei (2017).

The photographs of the artist shattering the urn are incorporated into “The Odyssey” artwork, but in this context the meaning is transformed. The breaking of the vase isn’t symbolic of destruction. Instead, it appears as an act of liberation, because it suggests the possibility of shattering a cycle that is devastating families and wrecking communities. Intriguingly, these photographic images have been recreated using Legos, which are designed to be taken apart and put back together in new configurations.

The painted vases in the gallery serve as incarnations of the progressive stages of the refugee plight, and so the images of the artist shattering a vase serve as a clarion call to break this tragic cycle. The work calls us to free people from the horrors of forced displacement, from relegation to camps that become prisons, from the hands of smugglers who sell them to the highest bidder. And then it asks us to consider what we will create in the wake of the breaking.

A God Who Shatters Oppressive Cycles

The shattering words of the prophet Isaiah speak to the reality that God himself breaks the oppression that binds people. “For you have shattered their oppressive yoke and the rod on their shoulders, the staff of their oppressor, just as you did on the day of Midian. For the trampling boot of battle and the bloodied garments of war will be burned as fuel for the fire. For a child will be born for us . . .” (Isa. 9:4–6a, emphasis added).

When Jesus stood in the synagogue and read from the scroll of the prophet Isaiah, he proclaimed his intention to break the chains binding the oppressed (Luke 4:16–21). Jesus’s words broke into the world to shatter the power of systemic and personal sin that dehumanizes all of us and creates the conditions of violence and extreme poverty that cause people to abandon their homes.

Jesus’s powerful proclamation of the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy is a creative force because healing and restoration follow in the wake of the breaking. His body was broken on the cross, but then it was raised to new life. As the first fruit of resurrection, he shows us in his own body that breaking paves the way to healing, that the shattering pain of crucifixion opens the door to eternal life.

A painting depicts refugees languishing in camps in “The Odyssey” by Ai Weiwei (2017).

What Will We Create?

The name of the artwork—“The Odyssey”—alludes to the title of Homer’s ancient epic poem that catalogues the perils of Odysseus’s journey around the Mediterranean Sea. The name suggests that the story of human migration and suffering playing out today is very old indeed.

It is a story that has been retold countless times. But the title also suggests to me that this story is a human creation—this tragedy is of our own making. Ai Weiwei asks us whether we have the imagination and will to rewrite the story.

After circling the columns of painted vases, I turned my attention to a white column made of stacked unpainted vases. Like a blank canvas it poses a question: What will we be part of creating? Will we allow this cycle to recur, or will we paint something new?

Are we resigned to watching this tragedy repeated or do we have the vision to imagine a different future? How could we reach out with practical aid that would help refugees recreate and reestablish their lives?

Here a few ways to begin rewriting the story

- Open your eyes to learn more about the extent of the refugee crisis. Pray faithfully in response to news reports about refugees while considering the way God wants you to be involved.

- Give generously to agencies experienced in ministering to refugees. Baptist Global Response (BGR) works to meet the needs of the sixty million displaced people in countries around the world through special projects tailored to the needs of local communities.

- Volunteer to serve overseas by working with local partners serving refugees. Contact BGR for current needs.

- Welcome refugees in your community. Begin by considering these seven practical suggestions.

Ai Weiwei on Porcelain runs until March 11, 2018, at Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul, Turkey.

Eliza Thomas is an editor and writer who has worked with IMB for more than a decade. She lives with her family in Central Asia.