The fifteenth-century playwright Feo Belcari once wrote, “The Eye is called the first of all the gates / Through which the Intellect may learn and taste.” This gallery continues a visual retelling of Christ’s passion narrative, picking up where Christ is given his cross (view part 1 here). The featured artists come from five different continents, and each one uses his or her gift of imagination to provide a gateway into knowing Christ and him crucified.

Jesus Carries His Cross

Jyoti Sahi (Indian, 1944–), Way of the Cross, 2009. Oil on canvas, 61 × 50.8 cm.

Now in a severely weakened state, Jesus is forced to carry his cross up Golgotha’s hill. This journey from praetorium to execution site is known in Christian tradition as the Via Dolorosa, “Way of Sorrows.” Way of the Cross is one of several pieces Jyoti Sahi painted during Lent 2009. It shows Christ traversing the Deccan Plateau of southern India, past the Tungabhadra River (you can see it snake down from the top right corner). Two of Jesus’s followers bow down in love and contrition. The Holy Spirit presides over the scene in the form of a hamsa, a swanlike bird from Indian mythology.

Raised by a Hindu father and Christian mother, Sahi runs an art ashram, a retreat center. His work traces the geographical and spiritual landscapes of India, with emphases on religious symbols and the Dalit experience. A doctor of divinity, he supplements his art practice with giving seminary lectures and publishing in the fields of theology and Indian Christian culture.

The Crucifixion

Lindiwe Mvemve (South African, 1958–), Crucifixion, 1977. Linocut. Collection of Haus Völker und Kulturen, St. Augustin, Germany.

The cup of suffering Christ accepts in Gethsemane he drinks to the dregs on the cross. In Crucifixion by Lindiwe Mvemve, this cup is enlarged to contain the Crucifixion scene itself, which shows Christ hanging between the two thieves, in the company of Mary, John, and an angel of consolation. God the Father holds this cup tenderly in his hand, looking in with sadness. He, too, felt pain on Good Friday—to see his son suffer. The greater implication of this linocut is that all human suffering is taken up into the hands of God.

Mvemve was one of the few female artists to have studied at Rorke’s Drift, an art school established in South Africa in the 1960s by Swedish missionaries. The staff concentrated their teaching on developing technical expertise, allowing students freedom in style and subject matter. When biblical subjects were chosen, it was of the artists’ own volition. Rorke’s Drift has been recognized by secular institutions for the positive role it played in promoting contemporary South African art, especially printmaking.

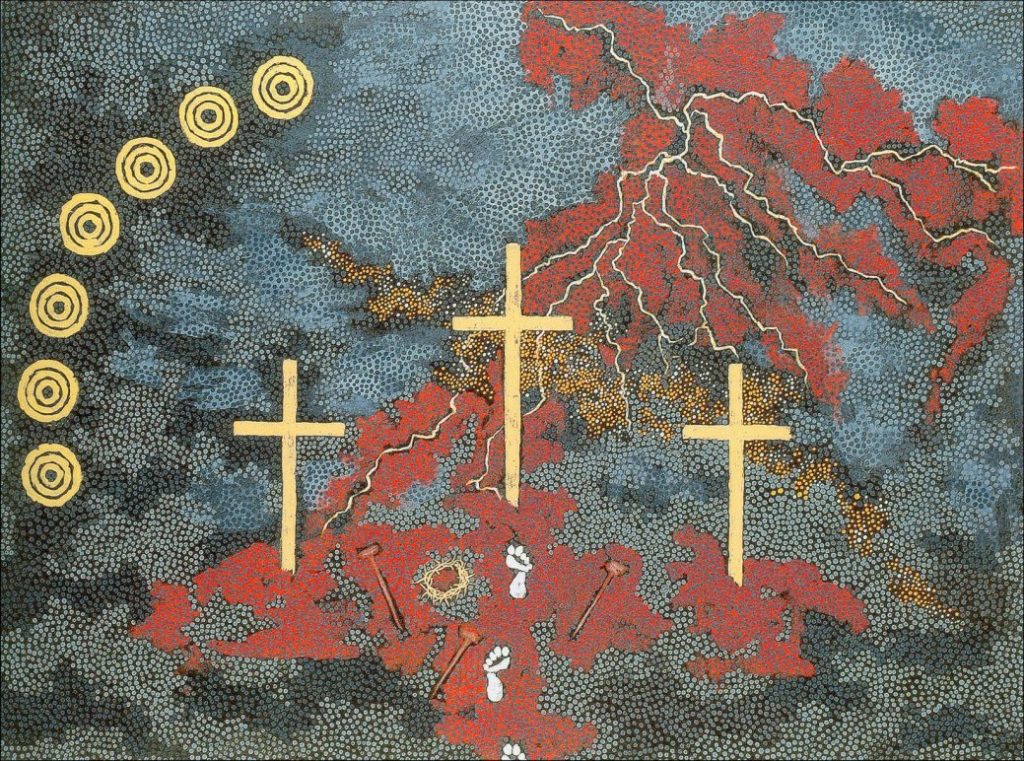

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (Anmatyerre, 1932–2002), Good Friday, 1994. Acrylic on canvas, 116 × 154 cm. Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Parkes, Australian Capital Territory, Australia.

While Mvemve shows us a cosmic perspective marked by tender sorrow, Aboriginal Australian artist Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri emphasizes divine wrath and punishment. The two images are not irreconcilable. The Bible gives us a complex picture of the meaning of the Crucifixion, and artists draw out different elements. In Tjapaltjarri’s long-shot view of Golgotha, a lightning bolt pierces through the roiling sky, coloring it red like blood. To the left, the Pleiades star cluster, known in Aboriginal mythology as the “Seven Sisters,” bears witness to the event. There are no bodies on the crosses, but a crown of thorns and three oversize nails allude to Christ’s presence. The footprints, which enter from the bottom, lead our eyes to the focal point: the cross to which our sins were nailed when they were taken up into the body of our savior.

Tjapaltjarri’s first exposure to Christianity was through a Lutheran mission station, where during a drought his family went to receive food. A pastor there noticed his severe malnourishment and took him to get medical treatment. Over a year he regained his health and also learned the stories dear to the Christian heart. He never fully embraced Christianity, but he maintained a deep affection for it and for the pastor who saved his life.

The Lamentation

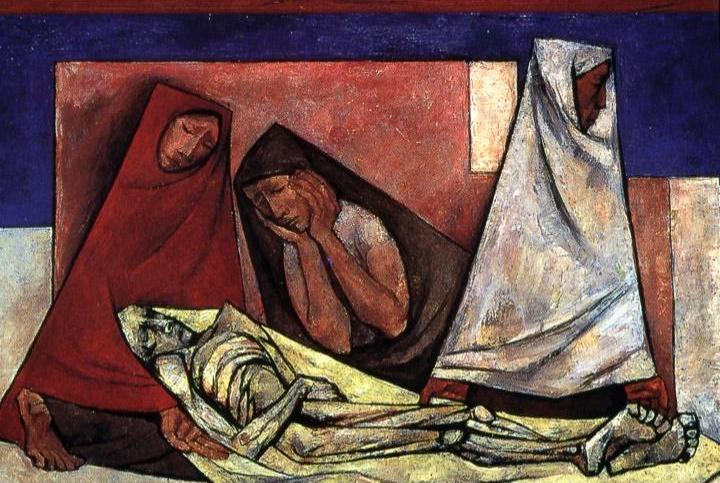

Oswaldo Guayasamín (Ecuadorian, 1919–1999), Fusilamiento (Execution by Firing Squad), 1943. Oil on wood, 80 × 120 cm. Collection of the Museo de la Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, Quito, Ecuador.

Oswaldo Guayasamín, an artist of Maya, Quechua, and Spanish descent, has been the most important Ecuadorian practitioner of socially and politically committed art. Inspired by his travels through Latin America, much of his work portrays the suffering of indigenous peoples and the human cost of war.

Fusilamiento (Execution by Firing Squad) depicts a dead young man lying naked on a sheet. Three hooded women care for and support him, having wrapped his wounds in linen, even as they mourn. One of them turns away, unable to confront the carnage and loss. The angularity of forms in the painting gives it a certain harsh expressiveness.

The ambiguity of the setting helps establish universality—this could be anywhere, this funeral. The composition is reminiscent of traditional Lamentation paintings, depicting the Three Marys mourning Jesus’s death at the foot of the cross.

The Dead Christ in the Tomb

Sergii Radkevych (Ukrainian, 1987–), Tomb of the Lord, 2011. Acrylic and aerosol on concrete. Polonyna Runa, Ukraine. radkevychsergii.wixsite.com

After Jesus’s body is carried to a donated tomb, it lies there for three days. This subject—the buried Christ—is a recurring one in the repertoire of Ukrainian artist Sergii Radkevych. Inspired by the visual language of icons, he adapts that language to a contemporary street art format, painting the walls of abandoned factories, barns, stone ruins, or whatever else he can find. Radkevych says he seeks out spaces that have lost their function or have an undefined meaning and transforms them into spiritual spaces. In the painting pictured here, an unused cement structure on a Carpathian mountaintop plateau becomes the tomb of the Lord. He hopes that people making the climb will stop to notice the image and consider the supreme sacrifice Christ made on their behalf, and be led to gratitude and worship.

The Women at the Tomb

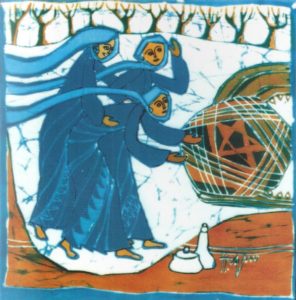

Hanna Cheriyan Varghese (Malaysian, 1938–2009), Who Will Roll Away the Stone?, 1999. Batik. www.hanna-artwork.com

After what was no doubt a gloomy Sabbath, some of Jesus’s female followers come to the tomb to finish treating his body with oils and spices. What they find will shock and amaze.

The batik Who Will Roll Away the Stone? by Malaysian artist Hanna Varghese emphasizes the suspense and excitement of this discovery. Three women in blue dresses and headscarves, whipped by a wintry wind, walk to the burial site of their friend and master. A sudden thought gives them pause: are they going to be able to move the heavy stone out of the tomb’s entryway? But when they arrive, their concern is for naught, because they find, to their surprise, that the stone has already been rolled away. They put down their jars and investigate.

Batik is a wax-resist method of dyeing pictures onto fabric. It was Varghese’s primary medium. Varghese was inspired by the Asian Christian Art Association to artistically engage the stories of scripture.

The Resurrection

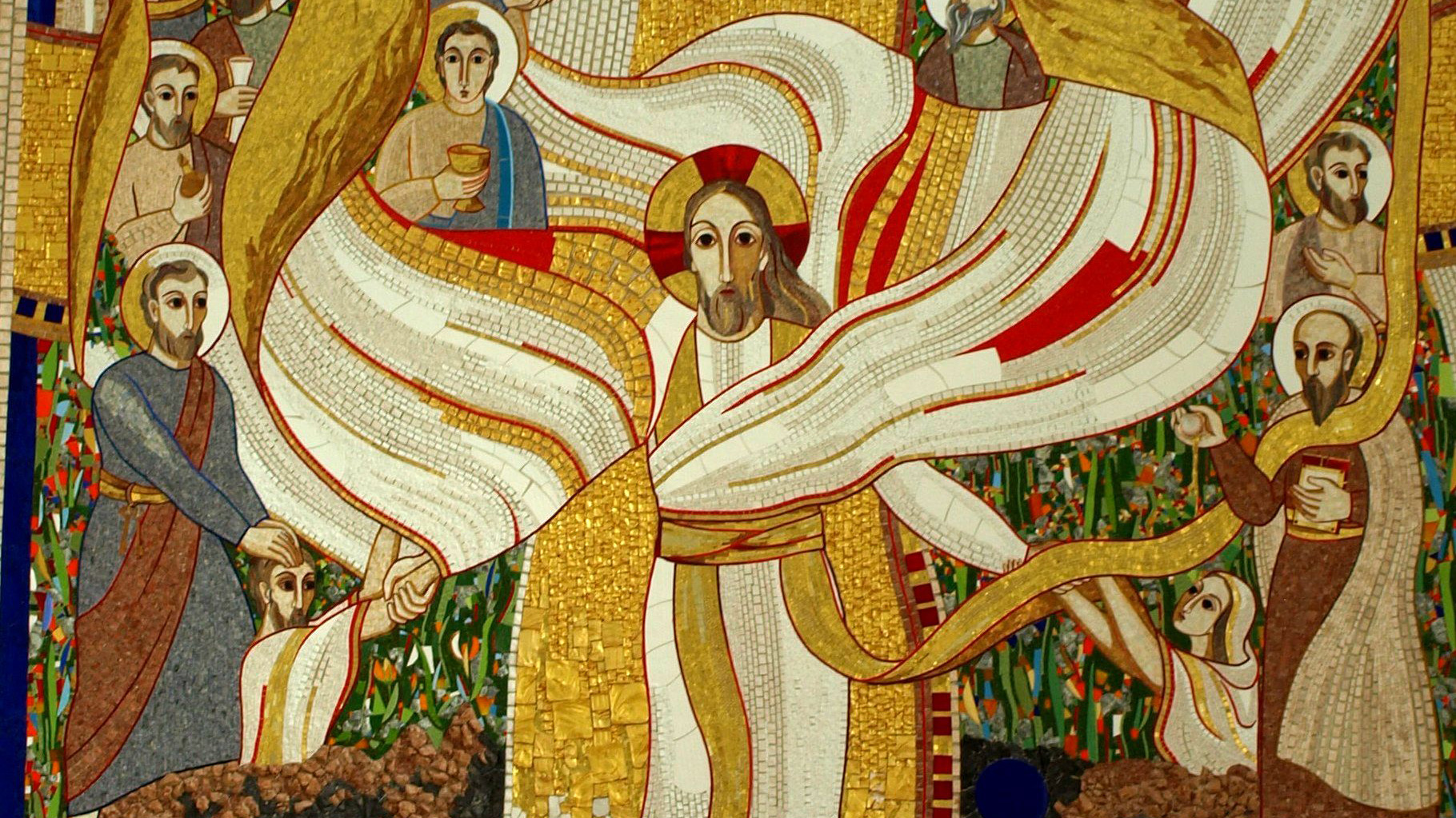

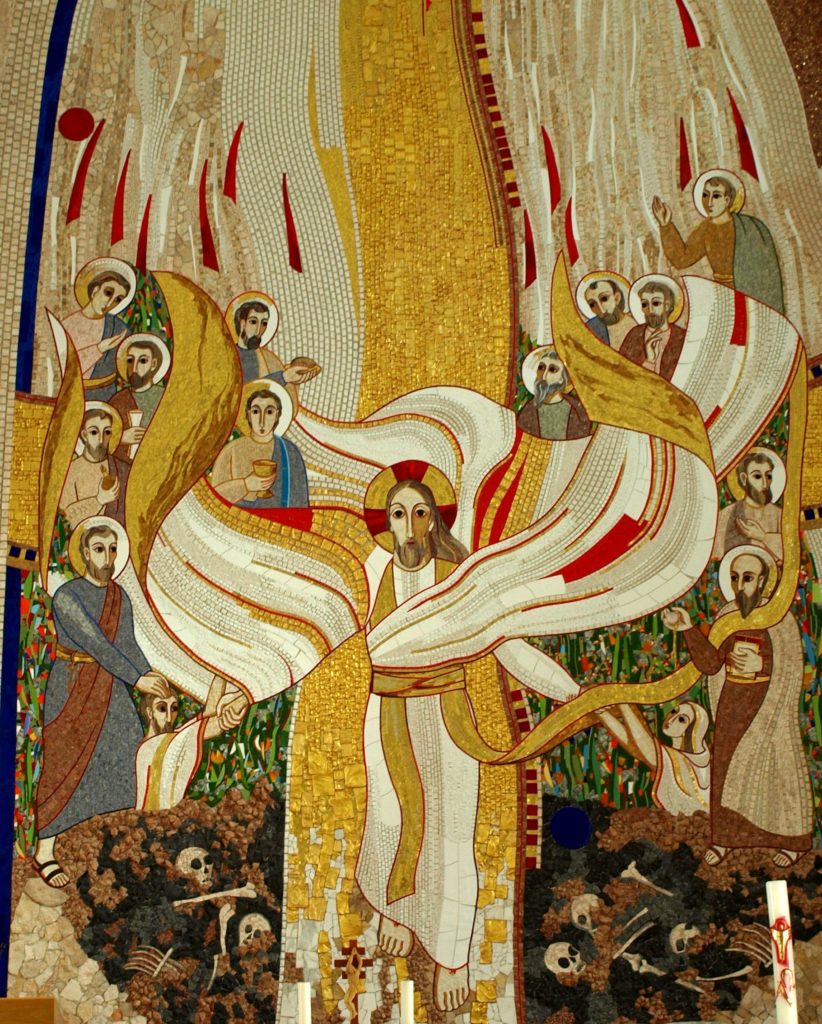

Marko Ivan Rupnik (Slovenian, 1954–), Resurrection of Christ (detail), 2006. Mosaic, St. Stanislaus College Chapel, Ljubljana, Slovenia. www.centroaletti.com

What the Marys discover is an empty tomb and, soon after, a risen, all-glorious Christ. Mosaicist Marko Ivan Rupnik envisions this pivotal event in salvation history as a glory-stream bursting up out of the belly of the earth, with Christ walking atop it, much like he did on Galilean waters, his robes billowing out in all directions. Victoriously, he pulls Adam and Eve up from their graves, up from the valley of dry bones, fulfilling the prophecy of Ezekiel 37. Tongues of fire fall from heaven, the Spirit poured out on the saints from all ages and nations, who, eating bread and drinking wine, are incorporated into Christ’s resurrection body. The vibrant greens and other colors behind this great ecclesial gathering signify a garden: new Eden.

In Christ’s resurrection, sin is redeemed and humanity is invited into new life.