Since the third century and maybe even earlier, Christians have made religious art. One of its main purposes was to serve, in the words of a fifteenth-century English clergyman, as “rememoratif signes or mynding signes”—that is, reminders of the ways God has acted throughout history in the lives of his people.

Most people tend to think of Western Europe as the major center of Christian art production. While it did lead the way during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Christian art flourished in other areas too. The earliest Christian art, contemporaneous with the catacomb frescoes in Rome, is from Syria (the walls of a house church in Dura-Europos).

Constantinople in modern-day Turkey was crucial to the development of a distinctly Christian iconography. Russia inherited the tradition of icons from this Byzantine capital and took it to new levels. Meanwhile, Armenia, Egypt, and Ethiopia were developing their own Christian art. India and Congo, too, after contact with the Portuguese, adapted imported imagery to their own cultural contexts, retaining the biblical content but introducing innovations in style and form.

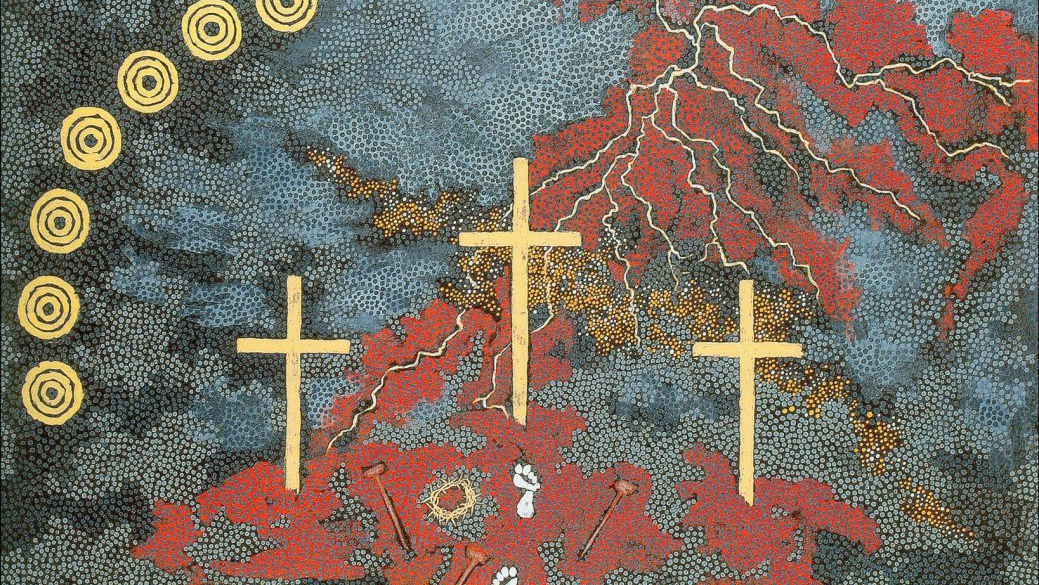

Artists from all over the world are still exploring biblical content through their work. The following pieces represent ways that modern and contemporary artists have imaged the passion of Christ. Some of them demonstrate cultural contextualization, a practice that has been around since the inception of Christian art. By translating Christ into new contexts, artists do not mean to undermine his historicity but rather to assert his relevance, his “with-us-ness.”

Jesus said in John 6:51 (KJV), “I am the living bread which came down from heaven: if any man eat of this bread, he shall live for ever: and the bread that I will give is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world.” The fulfillment of this promise—Christ given for the life of the world—is evident all over the globe, where the gospel vitalizes communities, finding expression in their spiritual and material cultures.

May the artistic giftings of Christ’s diverse body support us this season in our journey to the cross and beyond.

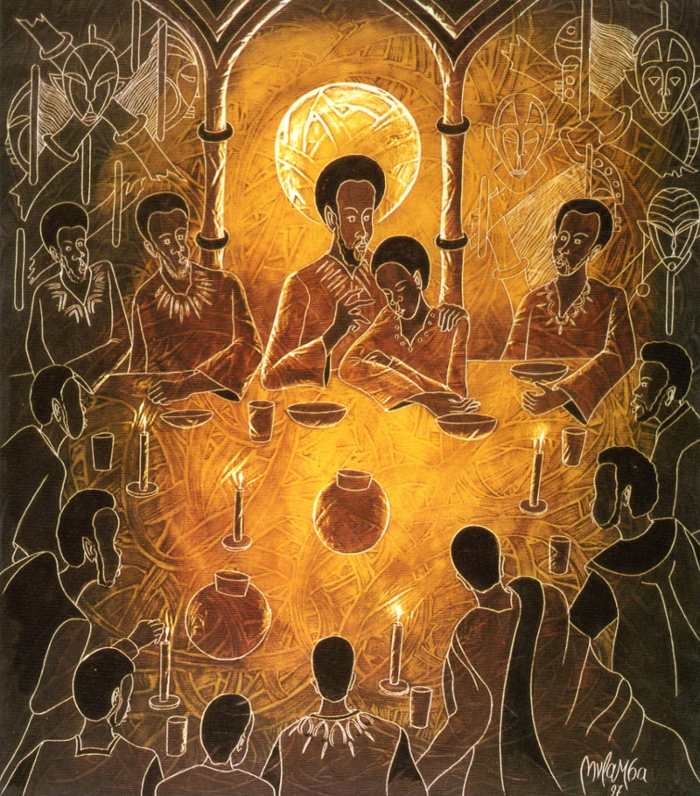

The Last Supper

Joseph Mulamba-Mandangi (Congolese, 1964–), The Last Supper, 1997. Peinture grattée, 70 × 60 cm. Collection of Missio Aachen.

In his painting of the Last Supper, commissioned by Missio Aachen in Germany, Joseph Mulamba-Mandangi represents Christ as Congolese, sharing a few jugs of palm wine with his disciples in a bamboo hut. The Twelve react to his announcement that one of them is going to betray him. The African masks in the background, rendered using a scratching technique, suggest that this meal is initiating an important transition, a rite of passage. Jesus will be passing from life into death, then back into life, and making this passage possible for the entire community.

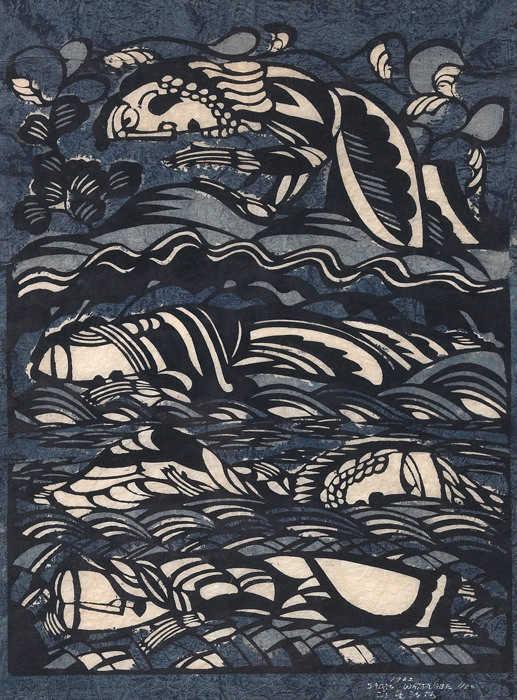

The Agony in the Garden

Sadao Watanabe (Japanese, 1913–1996), Garden of Gethsemane, 1962. Stencil print, 68.9 × 53.3 cm.

After a tense supper, the group sings a Passover hymn, then they go out to a nearby olive grove. Jesus distances himself from the others, wanting to be alone to pray. Sadao Watanabe, the twentieth century’s most celebrated and prolific Japanese Christian artist, responded to this episode with a multi-tiered stencil print showing Jesus kneeling on the ground, hunched over in distress, supporting his weight with one hand while raising the other to his face. In the lower tier, Peter, James, and John sleep soundly, contravening Jesus’s request that they stay awake and pray for him. The cool, muted, blue-gray tones imply darkness setting in.

Originally trained as a textile dyer, Watanabe was inspired by the mingei (folk art) movement to pursue a career in printmaking. He used a technique called katazome, which entails cut-paper stenciling and dyeing with a variety of natural mineral and organic pigments.

“I owe my life to Christ and the gospel,” Watanabe said. “My way of expressing my gratitude is to witness to my faith through the medium of biblical scenes.” To help correct the common misconception among Japanese that Christianity is incompatible with their national ethos, Watanabe sought to retell the entire narrative of scripture using a Japanese aesthetic.

“I owe my life to Christ and the gospel. My way of expressing my gratitude is to witness to my faith through the medium of biblical scenes.”

The Betrayal of Judas

Julia Stankova (Bulgarian, 1954–), Portrait of Judas, 2004. Tempera, gouache, watercolors, and lacquer technique on wood, 45 × 60 cm. www.juliastankova.com

While Jesus reprimands his disciples for their negligence, Judas presses in and bestows his infamous kiss. Bulgarian artist Julia Stankova portrays this moment as one of double woe, leading to the death of both Jesus and Judas. To heighten the emotional impact, Stankova tightly crops the composition, eliminating all other figures besides the two. Jesus closes his eyes to receive with grace what has been a long time coming. Judas keeps his open. With one arm, he embraces his former friend; with the other, he holds a branch that’s ornamented, forebodingly, with his own dangling corpse. The Bulgarian inscription names the painting: Portrait of Judas.

Sacred art has been a part of Stankova’s life since childhood when she first encountered the frescoes inside her grandmother’s church. The collapse of the Communist regime in 1990 enabled her to leave her career as a mining engineer and pursue art making instead. She learned a lot about Byzantine iconography by working as an apprentice to a restorer of icons, which inspired her to get a master’s degree in theology and to study the Bible more deeply. Stankova now specializes in Christian imagery. She’s not an iconographer in the technical sense because she doesn’t confine herself to the visual canon of Orthodoxy, but her work is heavily indebted to that tradition.

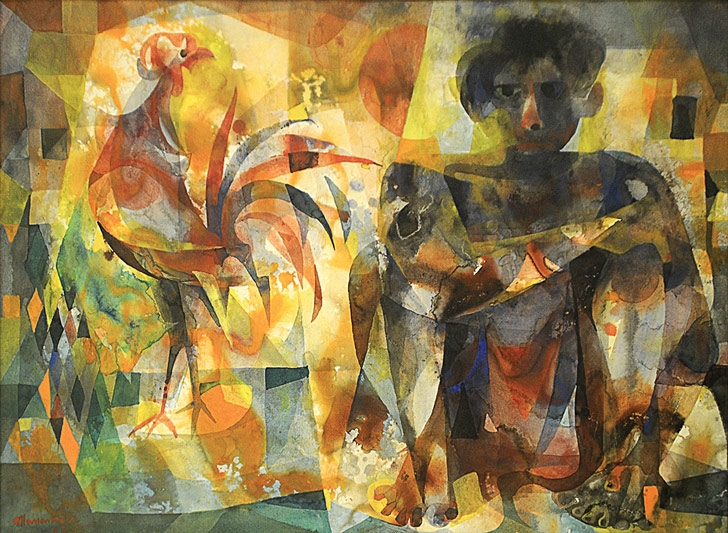

The Denial of Peter

Vicente Manansala (Filipino, 1910–1981), Man with Rooster, 1963. Watercolor, 58.4 × 78.7 cm.

Vicente Manansala is one of the “Big Three” modernist painters from the Philippines. He developed a style known as transparent cubism, marked by the geometric faceting of forms and the shifting and overlapping of planes.

A neo-realist, Manansala drew inspiration from his immediate environment, portraying the pleasures and pains of Filipinos in the postwar era. Jeepneys, shanties, rice planters, market vendors, children at play, families gathering for modest meals, and mother and child were among his recurring subjects. He also painted explicitly Christian subjects like the Crucifixion and the Pietà.

In Man with Rooster, it’s possible the artist intended for the man to be a sabungero (cockfighter). But the composition seems to bear deeper allusions to Peter’s denial: the rooster is bathed in light, an agent of revelation, whereas the man is colored black with shame, his eyes well with remorse.

Christ before Pilate

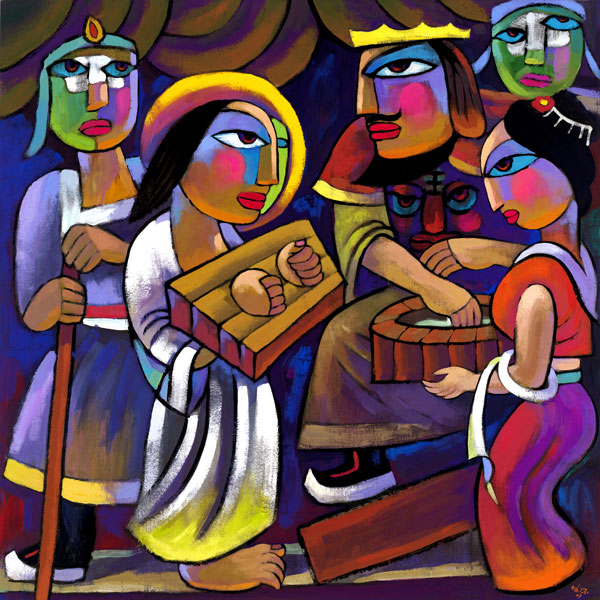

He Qi (Chinese, 1950–), Pilate Washing His Hands, 2007. Oil on canvas. www.heqiart.com

The first person in the People’s Republic of China to earn a PhD in religious art, He Qi (pronounced huh chee) blends influences from European medievalism, American modernism, and Chinese folk art in his vast body of painted work. Like Watanabe, he wants to show how Christianity can be at home in Asia. In his attempts to visually indigenize the biblical narrative, however, he has encountered pushback.

For example, a newly built church in his country commissioned him to paint a fresco. When he presented a design of the risen Christ, the pastor rejected it because it was “too Chinese” and requested instead that he paint a copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, which, in the pastor’s mind, was more authentically Christian.

His Pilate Washing His Hands shows Christ in wooden stocks, standing before his condemner. Three assistants stand by—one with a bowl of water, so that Pilate can wash himself clean of his responsibility in the matter. A face, resembling a Beijing opera mask, stares out at us from Pilate’s chest, a warning against complicity in mob violence.

The Mocking of Christ

Hrvoje Marko Peruzović (Croatian, 1971–), Ecce Homo, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 40 × 30 cm. www.peruzovic.com

Delivered over to Pilate’s soldiers, Jesus is beaten and mocked. In the portrayal of this humiliation by Croatian artist Hrvoje Marko Peruzović, Jesus’s face is elongated with grief, his cheeks sallow and sunken in. One eye is swollen shut; the other, bright blue, looks out, pleading for sympathy. Here Jesus is just a bust floating in a blood-red color field. Even his halo, his glory, is tinged with red. His strongly frontal pose compels us to behold him, the innocent lamb slain for our sin.

This visual journey through the story of Christ’s passion continues with a sequence of seven new images from the crucifixion to the resurrection. The painting in the header of this post is by Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, “Good Friday,” 1994. Learn more about it in Journey to the Cross: Part 2.

Art is a powerful tool for communicating the gospel around the world in various cultures—things like poetry and song.