Decades after their murder at the hands of an Amazon tribe, the legend of these five martyrs—Jim Elliot, Nate Saint, Pete Fleming, Roger Youderian, and Ed McCully—continues to inspire. Every time I drive through the parking lot of my home church in America, for example, I see Jim Elliot’s famous quote inscribed on the entrance: “He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose.”

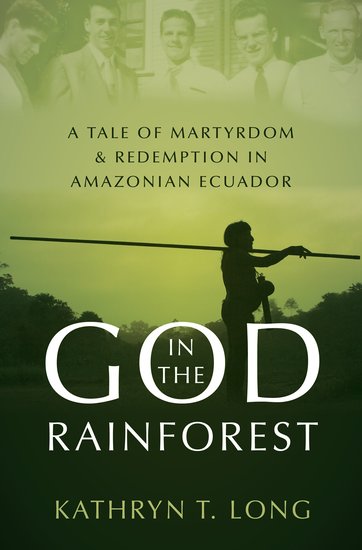

Kathryn Long, former associate professor and chair of the history department at Wheaton College, unfolds the story of their death and the subsequent decades of characters, personalities, and agencies involved in missionary work among the Waorani people in her book, God in the Rainforest: A Tale of Martyrdom and Redemption in Amazonian Ecuador.

The book sucked me in. Unbeknownst to me, critics over the years have severely condemned the actions of missionaries to the Waorani tribe, the people the missionaries tried to reach. Meanwhile, the five martyrs continue to hold an almost unshakable place of reverence in the evangelical Christian world. So which is it—are they good guys or bad guys? Long aims to present all the facts and leaves us sitting in a complex world without direct answers.

The book sucked me in. Unbeknownst to me, critics over the years have severely condemned the actions of missionaries to the Waorani tribe, the people the missionaries tried to reach. Meanwhile, the five martyrs continue to hold an almost unshakable place of reverence in the evangelical Christian world. So which is it—are they good guys or bad guys? Long aims to present all the facts and leaves us sitting in a complex world without direct answers.

Honestly, some chapters made me feel like a child who just found out Santa Claus isn’t real. I learned that some of my heroes, like Elisabeth Elliot, were complicated people who struggled on the field.

I think Long accomplished her goal with me. I’m left thinking about missionary work in a messy world with imperfect players. Here are some things I learned from this most engaging book.

Missionaries Are Complex People

Long explains the five missionaries made decisions that may have been powered by youth and zeal. For example, they were secretive throughout “Operation Auca,” the name for their efforts to contact the Waorani tribe. They never told their supervising missionary they were trying to make contact.

Nate Saint’s own sister, Rachel Saint, was a missionary under a different sending organization. She also focused on reaching the Waorani and was trying to learn the language through a language informant named Dayomæ. Yet Nate never told his sister about Operation Auca. Rachel found out about it only when she learned of her brother’s death.

“Missionaries are normal people.”

Rachel Saint pursued work among the Waorani for the rest of her life. She and Elisabeth (“Betty”) Elliot were focused in their desire to continue what God had put on their hearts. Yet they couldn’t get along. Differences in personality, theology, and missionary practice resulted in constant friction between them.

As Long points out, “One of the ironies of the reluctant partnership between the two was that, although officially Saint was the linguist and Elliot the traditional missionary, their apparent giftedness seemed just the opposite. Elliot had a knack and temperament for acquiring languages, while Saint exuded the activism and unquestioning commitment associated with evangelical missions” (91).

Their relationship deteriorated to the point that Saint began questioning whether Elliot still believed foundational Christian doctrines (109). Long explains that by the time Betty Elliot left Ecuador, “she had learned four languages, married, borne a child, been widowed, and lived in three different jungle cultures. In the American evangelical world, her reputation as a writer and missionary heroine had been established. But in Ecuador, her missionary experience had been characterized by loss” (131).

Isolation and Territorialism Is Dangerous

Rachel Saint continued in her work among the Waorani for the rest of her life. She was known to be tenacious and focused, yet she was also known to be stubborn and resistant to working with others. Long says that Rachel’s sending organization typically would never approve a single person to do indigenous work without a partner, but they made an exception for her. They allowed Rachel to work alone with her language partner Dayomæ, a Waorani woman who escaped from the tribe as a young girl.

Rachel showed a kind of ownership over the people, insisting she knew best and refusing to cooperate with other people and organizations. Over the years, a settlement was established and a church formed among the people. Rachel and Dayomæ domineered the Tewæno, the name of their settlement. Long says that the “most painful and toughest to resolve was the reality that Rachel and Dayomæ ran Tewæno in ways that were unhealthy for all its inhabitants—the other [company] workers and Waorani alike” (201).

Rachel’s control over the ministry reached a breaking point. Her company eventually put her on probation from working directly with the tribe. Then they recalled her to the US. At that point, she retired and lived in Ecuador independently until she died.

Problems of Dependence Come from All Sides

Many critics of the work among the Waorani talk about the dependence that was created by the missionaries, starting from the first gift-drops from the five martyrs and continuing through to the overwhelming strong hand of Rachel Saint, who approached with a matriarchal perspective. Years later, Saint’s own nephew, Steve Saint, pointed to the tribe as a “case study illustrating the dangers of dysfunctional relationships between missionaries and indigenous people” (336).

Yet Long points out this, too, was complex. It wasn’t just Rachel—her partner Dayomæ took an active role in controlling the people by creating a “patronage system with herself at the top” (180). And the people themselves fed into the system because they wanted to change. They wanted to become more like the Quichua people, who anthropologist Jim Yost pointed out were the “next step up on the social ladder” (236).

One of the most controversial issues relating to the Waorani was the cooperation between missionaries and big oil companies in relocating Waorani out of their oil-rich homeland into settlements. Long again points to the complexity of the situation. She writes, “Of course, the story was never that simple. Relocation to the protectorate may have helped to preserve the Waorani as a people by curbing the spearing vendettas, avoiding potentially deadly clashes with oil crews, and fighting contact illnesses through the availability of medicines. Still, for a time Christianity was practiced as little more than a means of social control. And the overcrowding led to genuine dislocation and suffering, food shortages, and the polio epidemic” (333).

“Praise God for entering our messy world through Christ.”

Oddly enough, there was also a sort of dependence from the American church, who wanted to see fruit from the deaths of the five martyrs. The missionaries felt pressured to show the deaths of the five men weren’t in vain. Every major anniversary brought renewed interest and desire to see proof that God was working.

Rachel Saint’s supervisor, William Cameron Townsend, was a visionary for fundraising who tapped into this need from the American church. He arranged for Saint and Dayomæ to fly to the US and appear on an episode of This is Your Life, viewed by an estimated thirty million people. Years later, Townsend again brought Rachel and three Waorani men to appear in mission rallies. There, they showed off the newly translated Gospel of Mark. Long points out that none of the men on stage, or those back in the settlement for that matter, could read. Despite this, the newly translated Scripture and the men on stage raised a lot of money from those who saw it as a redemption story (172).

Some Who Persevere in Faithfulness Will Disappear in History

The drama surrounding this saga sullied the pristine legacy I grew up with. Yet it didn’t destroy it. Long emphasizes that some people made decisions in good faith with bad consequences. Life is messy, and sometimes you can’t easily trace unwanted results back to only one person or cause.

In the final pages of Long’s book, she highlights two women who completed the full New Testament translation. Catherine Peeke, an American, and Rosi Jung, a German, were linguists. They came from different cultures, yet they worked together for years, avoiding publicity and persevering as a team until the final manuscript was complete.

To the church in America, this was a big victory. Christianity Today published an article called “Jim Elliot’s Legacy Continues.” Peeke and Jung, meanwhile, attended the two dedication events, unceremoniously standing in the back.

Long doesn’t draw a lot of conclusions from the complicated story of missionary work to the Waorani in Ecuador other than repeatedly saying things aren’t as simple as we tend to make them. I was encouraged by the example of Peeke and Jung who persevered outside the limelight. They knew that missionaries are normal people. Peeke described missionaries as “an imperfect, failing lot” who are “motivated to make [Jesus Christ] known to those in need” (333).

As a missionary myself, I can only agree. Praise God for entering our messy world through Christ. And at the end of the day, that’s where I’m going to put my trust.

Madeline Arthington is a writer who serves with IMB in Central Asia.