When the angel Gabriel visited Mary to tell her she had been chosen to carry “the Son of the Most High,” she understandably wondered, “How can this be?” The angel reassured the anxious young woman with a promise: “For nothing will be impossible with God” (Luke 1:37 HCSB).

Nothing will be impossible with God. The incarnation is the doctrine of the impossible becoming reality. It’s the belief that the eternal Creator took up residence in a finite human body. Divinity mingled with humanity—the two natures were equal and inseparable in one person named Jesus Christ.

In John’s summation, the incarnation is the belief that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14 ESV).

“Decorative Nativity” by Wisnu Sasongko, 2014, Indonesia. Acrylic on canvas. Available for purchase from the Asian Christian Art Association.

The incarnation affirms that God became one of us. He breathed our air, shared our space, and felt the ground beneath his feet. He tasted milk and honey, smelled bread baking, and drank cool water. He was nursed, swaddled, cradled, rocked to sleep, beloved. He dipped his toes in the Jordan River, saw the sun rise in the morning, and listened to the waves lapping on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. All the while, he was the “image of the invisible God” through whom the world had been created (Col. 1:15–16).

It’s a truth too big to take in, but it’s what Christians believe. And Christian artists around the world help us see this truth in all it’s impossible beauty.

Divinity Mingled with Humanity

Early church fathers agreed at the Council of Chalcedon that Christ was “in two natures without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” They affirmed that Jesus was both divine and human—fully God and fully man—and that these two natures were indivisible.

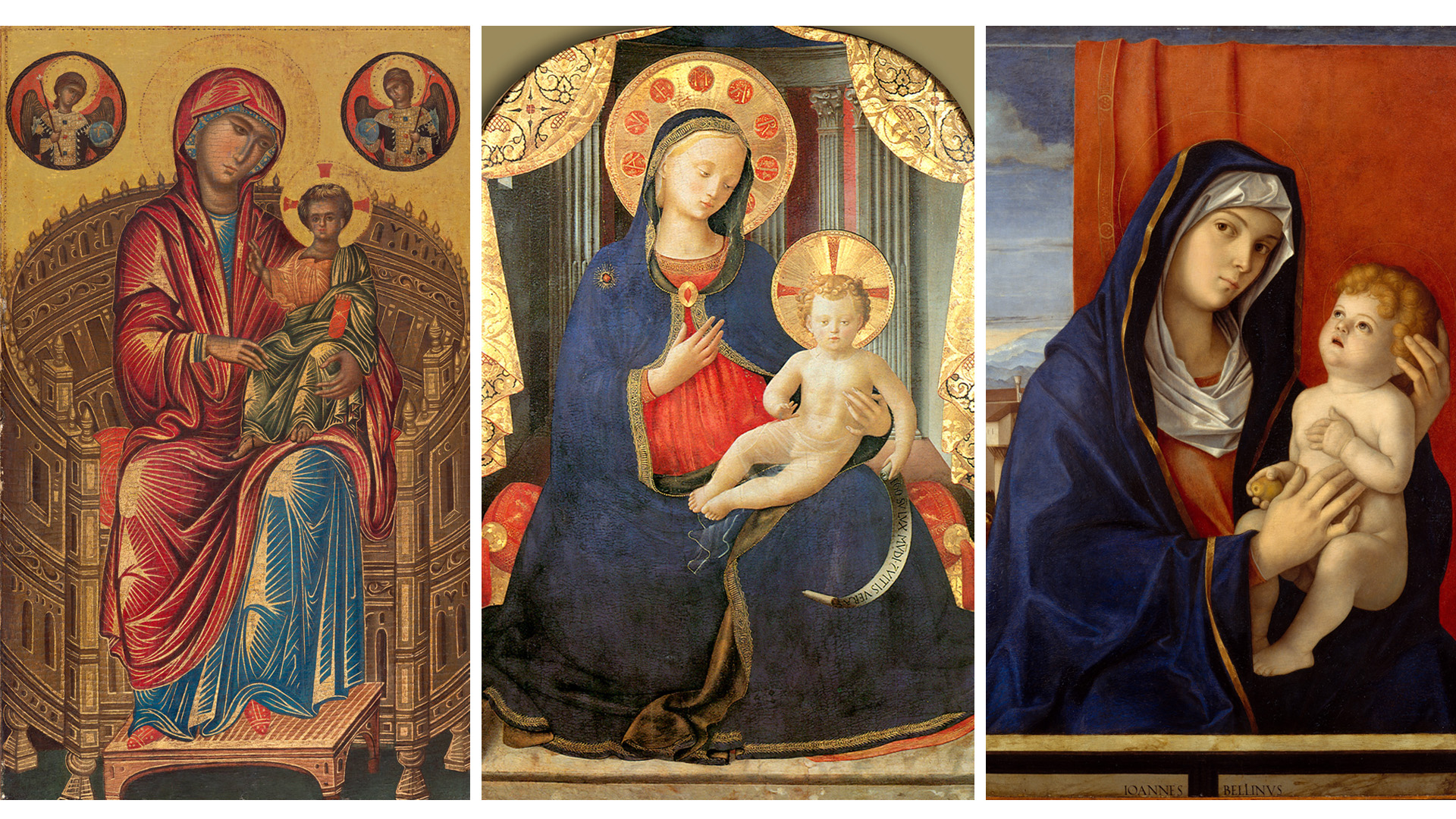

Christian artists, then, were left to wrestle with the challenge of representing both the divine and human aspects of the person of Christ. Eastern artists tended to emphasize the divinity of Christ while Renaissance humanist painters often portrayed Christ’s humanity. But the ultimate goal was to fuse the two together in a unified whole enabling us to see both the glory of God and the Word made flesh.

Left: “Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne“ (1260/1280). Byzantine, at the National Gallery of Art. Center: “Virgin and Child” by Fra Angelico (1428–1430). Italian. Right: “Madonna and Child” by Giovanni Bellini (late 1480s). Italian, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The red cloth of honor is pulled aside to reveal a distant landscape. The transition from a dormant to a verdant nature and a dawn sky is a metaphor for death and rebirth.

There was no better way to emphasize the human aspect of Jesus’s nature than by showing that he had a body just like ours. Artists often painted baby Jesus naked because nakedness—revealing his flesh—was a powerful assertion of the theological truth that he was fully human.

“Madonna and Child” in a Landscape by Giovanni Bellini (1480/1485). Oil on panel. Italian, Ralph and Mary Booth Collection.

Incarnation as New Creation Moving toward Redemption

The incarnation signaled a new creation embodying the hope that God entered our world to redeem us from the ravaging effects of sin and death. The idea that the Maker became matter was seen as initiating a new world order moving toward total restoration.

Historian Jaroslav Pelikan explains that, from the orthodox perspective, the “new order” of creation that had been initiated by Christ’s incarnation and sealed by his resurrection had “affected all of human life and thought, also every branch of metaphysics, including not only ethics but aesthetics.”

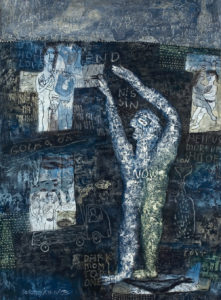

“A New Man” by Wisnu Sasongko (2003). Indonesia. Available for purchase from the Asian Christian Art Association.

Among other things, the definition of the incarnation doctrine made the formation of a theory of Christian art possible. In the seventh century, John of Damascus, a Syrian Christian who penned the first defense of Christian art, explained: “Of old, God the incorporeal and formless was never depicted, but now that God has been seen in the flesh and has associated with humankind, I depict what I have seen of God. I do not venerate matter; I venerate the fashioner of matter, who became matter for my sake and accepted to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation.”

A Historical Birth That Transcends Time and Culture

Jesus was born on a particular day, at a particular place, and within a particular cultural context. But the significance of his birth transcends a particular historical moment. Since the incarnation of Christ has significance for all people, at all time, and in all cultures, artists have often imagined the birth of Jesus within their own cultural context.

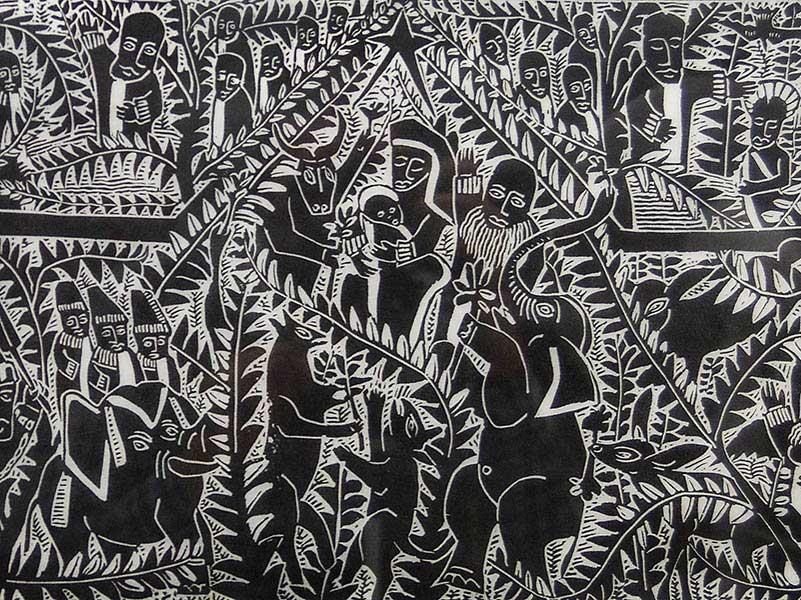

“African Nativity” by Azaria Mbatha. South African. Available at auction from Mutual Art. Mbatha shows us that all creation rejoices at the coming of this child.

Artists portraying Jesus and stories from his ministry on earth may wrestle with the balance between the historicity of his life and the meaning it carries for all of humanity. In the Netherlands in the mid-fifteenth century, Rogier van der Weyden painted the nativity peopled with Europeans in silk and brocade finery. Korean artist Woonbo Kim Ki Chang painted Mary and Joseph wearing traditional Korean clothing. And South African Azaria Mbatha imagined elephants gathered around the manger. All are foreign to the historical reality of Christ’s birth in Palestine. But though these aren’t accurate representations of the historical event, all proclaim the wonder of the birth of incarnate God within their own cultural contexts.

Envisioning Christ in a Korean, African, or aboriginal setting is no different than imagining him in an Italian countryside or a Dutch palace. Western depictions of Jesus tend to be less controversial than Eastern, African, and South American images only because they are more familiar, not because they are different in kind. Jesus was no more European than he was East Asian or African.

“The Nativity” by the Workshop of Rogier van der Weyden (mid-fifteenth century), Belgium. Tempera and oil on wood. The Cloisters Collection, 1949. On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 627.

Incarnation Contextualized within Culture

Controversy often surrounds contextualized images of Christ because some fear the accuracy of the gospel message is at stake. Goan artist Angelo da Fonseca was condemned and expelled from his country by the Portuguese Colonial Government when he painted the Virgin Mary in a traditional Goan sari.

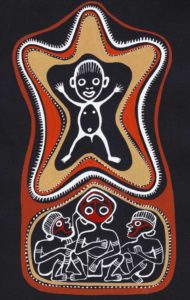

“Ner Wiynmaiy” by Nanias Maira (2011). Painting on sago palm bark. Kwoma/Papua New Guinea. Photo: Peter Brook. The star signifies the prophecy of Christ’s birth and the three figures represent the magi who traveled to Bethlehem to worship the new king.

But even if contextualization of Christian imagery raises significant issues, expressing gospel truth in local, visual languages is essential in helping people understand the meaning of the good news, recognize its relevance for their lives within their own cultures, and embrace it as their own.

Peter Brook, a Wycliff Bible translator, worked with Nanias, an artist from Papua New Guinea, to create a set of illustrated Bible stories that were faithful to Scripture while using visual language familiar to the Kwoma people. When Kwoma villagers saw Nanias’s paintings, their enthusiastic response was, “These are ours!” The Bible was no longer seen as foreign because “The paintings in their local visual language spoke straight to their hearts.”

Jesus for Every Culture

Thai artist Sawai Chinnawong celebrates Jesus’s relevance for every culture. He explains: “My belief is that Jesus did not choose just one people to hear his Word but chose to make his home in every human heart. And just as his Word may be spoken in every language, so the visual message can be shared in the beauty of the many styles of artistry around the world.”

“Nativity” by Sawai Chinnawong (2004). Thailand. Acrylic on canvas. Available for purchase from the Overseas Ministry Study Center.

And yet, sometimes the closer to home we bring the idea of incarnation and the story of the birth of God, the stranger it seems. This year a hipster nativity has been stirring up controversy—the wise men carry Amazon boxes and the Joseph takes a selfie with Mary. The lack of reverence for a holy moment may make this visualization of the birth of Christ seem like a joke. Perhaps it is.

But we could see in this modern nativity a critique of contemporary culture or a commentary on the commercialization of Christmas. In America we’ll market anything, including the birth of a Savior. Or we could read in it a subtle, probably unintentional, affirmation that this story is for us today—for hipsters, delivery guys, and digital natives.

Whether we live in Portland, Papua New Guinea, or Pretoria, this story is for all of us.

Refujesus by Zeljko Uremovic (2000). Zagreb, Croatia. Detail from a book collaboration with Boris Peterlin, a series of paintings portraying Jesus’s birth, flight to Egypt, and return to Israel.

You can see more nativity scenes by artists around the world here.